In my previous post, I discussed the importance of separating wealth from income, and to stop beating up a chap called Rob Barber who made the mistake of having a high income but not feeling rich. I get exactly where he’s coming from because I’ve been in the same position. In fact, it was more dangerous, because I made the mistake of thinking I was rich before having a sudden epiphany.

In the hazy distant past of my life, I worked at ICI from 1987 to 1997. It was a good ten years, in many ways, because although it started skint I acquired the skills and knowledge to make life a lot better for myself. I didn’t appreciate it as much as I should have done at the time, but in part because being skint at 18 is equivalent to trying to get out a pool of oil. Slippery and error prone.

In that time at ICI, and in the years when I left to become an IT consultant, I worked on payroll software and corporate financial software. When you code something into software, you have to know the subject intimately. Everything I code, I learned about in great detail then explained to a dumb computer. Programming is a really great way to understand things – a computer is like a very patient, dim student with fantastic memory. And when you teach, you learn. You have to.

So I remember when I was around twenty-five some of my older colleagues would always go on about how they hoped for early retirement. This seemed dreadful to me, because I remember my grandmother’s retirement in poverty. But what I didn’t know was how much things had changed.

These colleagues, you see, had a defined benefits pension scheme and ICI was a company on the wane. It needed to reduce headcount each year. One way that a department could reduce headcount was to retire people early, as young as fifty. Today I’m fifty and the idea of retiring and not being poor just isn’t there. I’d be quite hard up. So how could these guys get excited at the idea?

Defined benefit (DB) pensions vs. defined contribution (DC) pensions

All those guys retiring in the nineties onwards were born around 1940 onwards. They started work sometime around the early to mid sixties. And they won life’s lottery big style. They had two key things going for them. 1: the economy of the country was growing fast after the war, so there were lots of opportunities for work, and 2: because of a difficulty in hiring people, firms needed to find ways to attract and keep staff that was cheap at the time and hopefully kept wages down a bit.

At ICI, we were all on what’s known as a “defined benefit pension.” That means that the pension you get is defined according to a set of rules. If I remember rightly, the rule at ICI was quite simple – you got 70% of your final salary. This kind of final salary scheme exists today in only a few legacy situations or with older staff in some firms.

I remember thinking how it was crazy that a 50 year old with thirty years of experience could then look forward to another thirty years on 70% income. Given the reduced costs of retirement (no commute, no need to keep smart work clothes, etc) it was almost like having a full salary. Not only that, many would take a consulting or part time job and be on substantial incomes. They would earn more money in retirement than they would during their working careers!

I smelled a rat! The maths didn’t work out. As I then worked more and more on corporate finance I got to know a lot of accountants and some financial directors. I asked about this problem and they all said one thing: “Those pensions were promised to people by directors who are long gone, and mostly now dead. Totally unaffordable and the company now has to make up the gap… or go bankrupt.”

If you’ve ever wondered why so many of the giant companies of the UK that existed in the sixties are no longer with us, then that’s one key reason. Pensions. At one point, Rolls Royce was putting over a third of its gross profits into pensions. British Airways was once described as a massive pension company with a small airline attached.

This problem was known about in the seventies, but few people discussed it. It was brushed under the carpet. If you have some time, I highly recommend reading this 1975 letter from Warren Buffet on the subject of pension funds and likely shortfalls.

Moving on to your situation today – now you have a defined contribution scheme, if you start a pension scheme. It’s generally a good idea to have a pension scheme, especially because the UK government encourages it with generous tax breaks on contributions. Both you and your employer can contribute, within limits.

A defined contribution scheme (DC) is based on the money you put in, and that’s it. In many ways, that makes more sense. But how does saving a portion of your salary get you close the pensions your grandparents or parents got from large employers like ICI, universities, and the public sector? A hint… it doesn’t.

The great wealth shuffle

What’s happened, and it’s absolutely not the fault of the benefactors, rather than of cynical weasels that are long dead, is that wealth has been shuffled to the older generation in a very effective way. Not all older people, sadly, but those who had decent jobs in decent employers and owned their own homes did best, whilst those in more casual employment, rented their homes, and didn’t realise the importance of savings are left with nothing more than a state pension… so they did the worst and can still be in relative poverty. Unfortunately, if you’re not thinking and acting carefully today, your retirement, even if you work in a good employer, could be a lot more like that poor old person’s than you think and a lot less like your grandparents with their motorhome and three bedroom house.

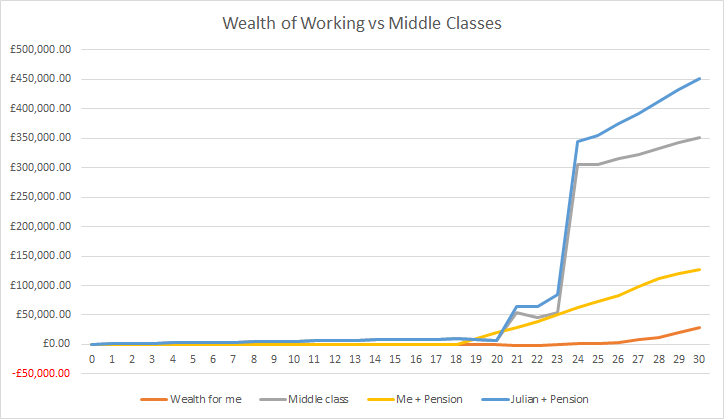

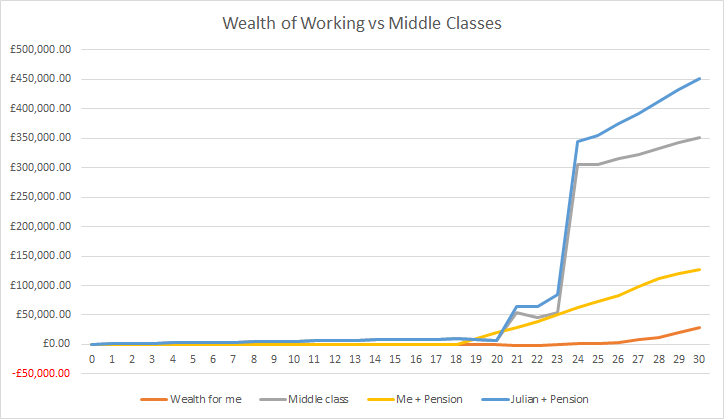

So, I like charts, right? Remember this one from the last article?

That shows my wealth including the value of my property, savings and other bits and bobs like a car up to the age of thirty, with a different line for a middle class person with the same career.

Let’s see how that changes if we take into account the defined benefit pension scheme I had at ICI. I then didn’t contribute to a pension scheme until I was in my forties, mainly because I had other priorities and, well, I knew what I was up to. But for most people that would be terrible advice. Don’t do as I did!

Take a look below:

Now, do you see the change? In fact, for one glorious year in this story I was ahead of the middle class chap called Julian from the previous post! It wasn’t to last, because we’re assuming he worked in the same way I did and had the same sort of career, just a few years later.

Just so you know, I worked out the pension wealth on a simple basis – it was worth, based on my leaving salary, the equivalent of £100k if I tried to buy an annuity, because today, to give the benefits I can still expect from my pension, I would need about a £200k or so fund in order to buy an income equivalent to my defined benefit. I hope that makes some sort of sense. In essence, I count my pension scheme as being a £200k bit of wealth that I don’t think about.

Defined benefits pension schemes made people who started work before the mid-nineties surprisingly wealthy. It’s just not fungible.

What does fungible mean when it comes to assets? It means that the money isn’t readily available. A bicycle is fungible. You sell it for cash, and can sell it quickly. A house isn’t terribly fungible, but still better than a pension scheme because the pension scheme is sort of a bet. It can release some money to spouses, but doesn’t necessarily have to – that depends on that defined benefit.

So my ICI company scheme increased my effective disposable income in those years by more than 100%. I never even realised it at the time, because I only really learned properly about money in my early thirties.

So now you know how that sweet little old lady with the poor education, who worked at a factory, has managed to afford a decent pension with three annual holidays and a mobile home near Carnaerfon.

So this is good, right? We made older people richer!

It is fantastic that older people were made richer. The only slight fly in the ointment is who paid. And why. And why it could be better.

First of all, remember above I pointed out that companies had big shortfalls in their pension funds? Well, if they had to find £5,000 for each year that I worked extra, that had to come from somebody who currently works at the company, and from the dividends. But if all big firms cut dividends, all pension funds (which hold shares in big firms) would have had even bigger shortfalls! And share values would have gone down, making these firms vulnerable to aggressive takeovers.

Reality is, and this is all a layman’s explanation without too much detail, that younger people paid to make older people richer, but without having the same future benefit for themselves. The older generation, realising the problem, and now running companies, took away those benefits wherever possible.

Pension funds also being large shareholders and needing their income, also pressured companies they held shares in to return greater profits! So that meant that younger people’s incomes were pressured in another way!

At least young people have avocados now?

Well yes, they have access to avocados. But not houses – they’ve become more expensive, because with people living longer, and fighting any development that may affect them and their neighbourhood, young people can’t afford houses. A starter home in my home town of Widnes is around £200k. That’s a *lot* of avocados you’re going to need to cut back on to make a dent in the wealth differential. Relatively speaking, my grandmother bought a brand new starter house for £17,000 in 1984. Which is about £55,000 today. Good luck buying anything other than a tiny ruin in Widnes today for that sort of money.

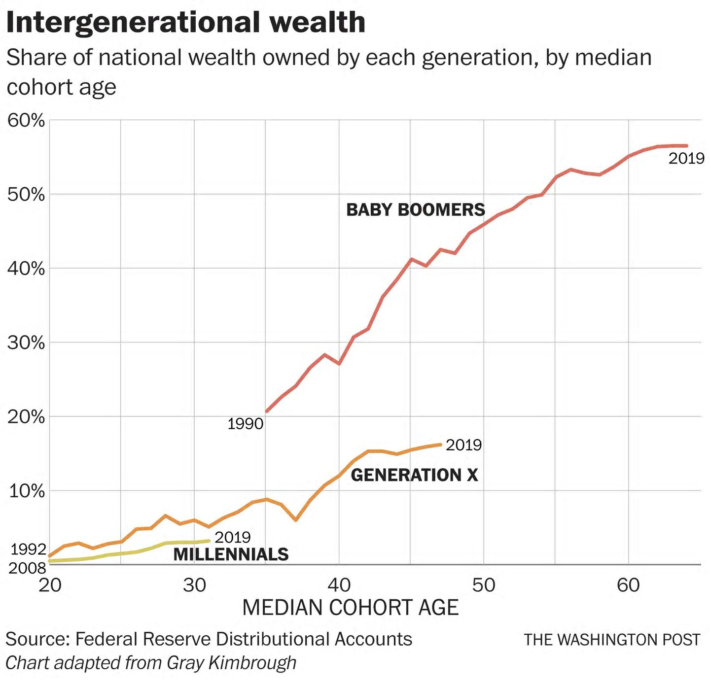

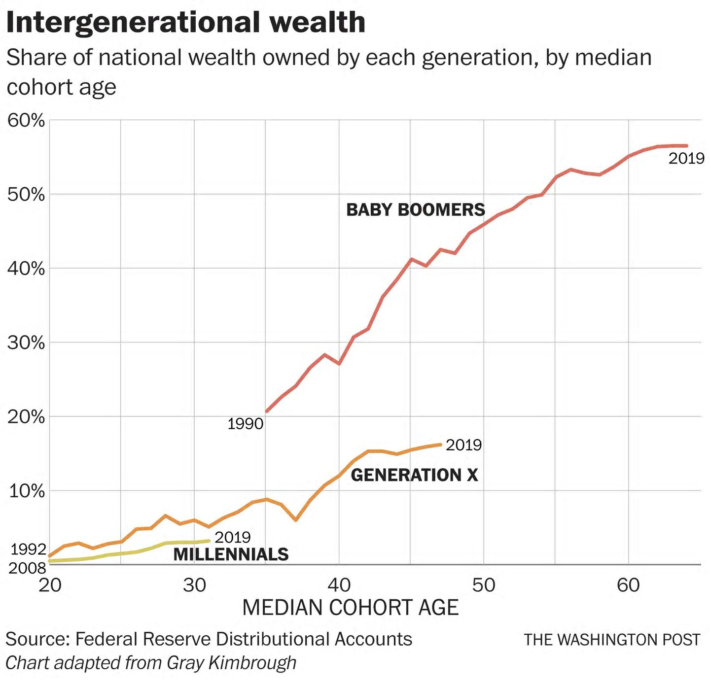

Houses and pensions have led to the following interesting chart:

Now, this chart has its caveats, and I recommend reading the full article here, but let’s face it, with these sorts of gaps, Rob Barber is going to have to earn £85k (a lot less after tax) in order to catch up with a well established boomer. And let’s not discuss how much harder it is if you’re working class and end up supporting the boomers that didn’t do so well on the pensions lottery and had more casual jobs. Life is harder if you started poor.

Photo credit: Photo by Matthew T Rader on Unsplash