About a decade ago, I was at a conference and talking to a fellow developer (I still call myself one, even though I don’t code so much these days) when he giddily told me about the funding he’d got for building a new piece of software he was hoping would make it big. It was a two year project and he’d got £100k funding. I asked if it was just him… and no, he had a colleague. So £100k, for two people, for two years? £100k didn’t sound a lot… £25k/yr each, basically. Or what you can earn in a much simpler tech support role. I decided not to say anything and leave the poor guy in peace, although this sort of work seemed a lot like gambling to me.

Today, things are different although there’s still a sniff of gamble about it overall. If you’re a developer it’s relatively easy to find a highly capitalised employer that’s positively dripping with money who will pay you £60k-£90k a year. Potentially quite a bit more. This reminds me of the late nineties dotcom boom. In 1997 I myself quit my safe but somewhat dull job at a multinational to become a freelancer, doubling my income almost immediately, and quadrupling it another year later. The new work was, in some ways, more interesting. It was also a lot more stressful, bad for my health, and definitely wasn’t the most exciting coding work. But it paid. I honestly don’t blame developers who decide to do what I did 25 years ago. It set me up. I think it was also a large part of why I had a heart attack in 2019… living out of hotels for a decade wasn’t healthy, and cheese became far too much a food staple for me as a vegetarian. However, the money was very good and it helped set me up. When you’re poor, it’s very hard to catch up and a good income was necessary for a while.

I bring this up because today I’m not ‘just a developer’ but actually run a web development company that specialises in websites and custom software for clients. And things are happening today that are reminiscent of the dotcom boom on the late nineties. 25 years have passed, but people don’t really change nearly as much as you may think.

The dotcom & Millennium Bug era

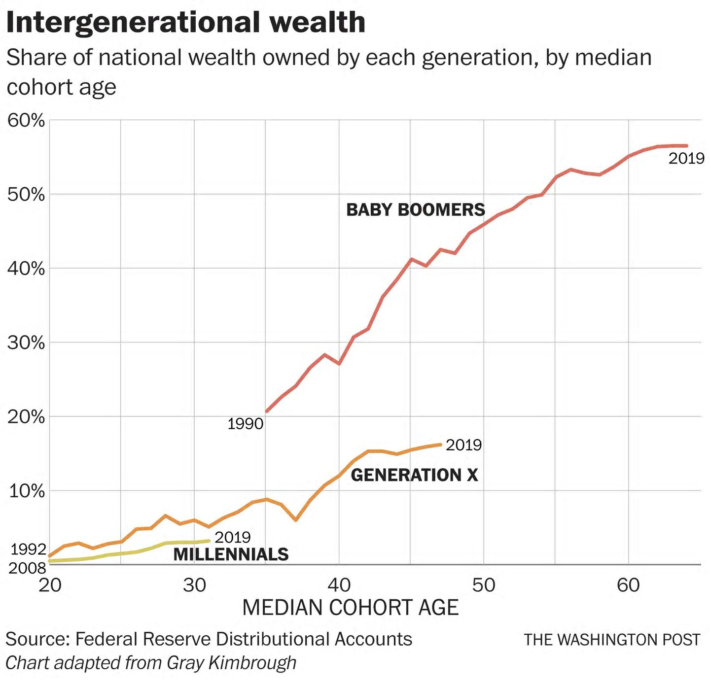

The late nineties were a period of post-recession growth and capital release. Banks had been deregulated, money was being created in the way it can be, and we were riding high on increasing productivity. Life felt good. And when money is created it can be invested.

There’s only one little problem in that. Sometimes, people get giddy and start splashing the money out too readily. The boom of the late nineties and early noughties, and the deregulation that encouraged it around the world, eventually led to the financial crisis of 2008. I’m a bit of a cautious soul, so even though I had plenty of income, I resisted borrowing too much to get a bigger house. In some ways I was foolish, because I could now be living mortgage free in the house I have now. But I figured that not having a big mortgage would afford me some other freedoms and I could use my money elsewhere. Mostly I just invested my money in solid companies. Friends, however, were telling me to invest in dotcoms. But I looked at the fundamentals. One example was a firm called Vocalis. They did, basically, telephone voice services software. Small team, and had some crazy valuation that was effectively equivalent of £20m per member of the staff. I rightly reckoned that was mad. My friend went ahead and pumped money in, and I mocked him. For a while I looked a fool. The value of the shares rose and rose.

Right now, there are loads of speculation bubbles. At the café at work I was trying to explain Bitcoin’s fundamental problems to our barista, when our receptionist came over excitedly wanting to know more. Both seemed interested in getting involved. That means the crash is likely imminent. They’re both lovely people, but in the economic chain, they’re nowhere near the top, which means that the speculation bubble is reaching it’s limits.

“If shoe shine boys are giving stock tips, then it’s time to get out of the market.” – Joe Kennedy, 1929 as the stock market was about to crash and lead to the Great Depression

So the dotcom boom and Millennium Bug led to a boom in demand for developers. New software was being created to replace supposedly outdated software that couldn’t be fixed (narrator: “It could”) and salaries were rocketing. I took advantage of that boom. I also knew it wouldn’t last. And it didn’t. My day rate as a PeopleSoft developer went from £200 a day in 1997 to £600 in 2002. It could have been higher. Cisco did an amazing job of raising funds in that era and I remember they kept offering me more and more to go to work for them in the Netherlands. But I didn’t really want to go to work there. I never really chased the money, so that’s about where I peaked. But I remember people with the right skills, experience and self confidence were on as much as £1k a day. That’s getting towards £2k a day at today’s prices. Some skills seen as super hard and rare could command double that. Most people didn’t, of course, make nearly that much, and some people preferred a job with reasonable hours and close to their families – a very valid and decent decision. But I was single with no ties.

There are a lot more developers around today – good incomes have brought many people into the trade. I meet people who called me a nerd in the eighties and now they’re working in IT. It’s a bit weird.

Today’s situation

Now it’s a bit weird. Rates still aren’t at the dotcom level, once adjusted for inflation, but they’re close. You can do very well in tech. But in my little firm we pay typically around £40k for a developer, plus various benefits, kit, resources etc, meaning you’d need to make around £70k as a freelancer to equal it. At least the way I calculate things and always did. I nearly swapped my £600 a day for £60k a year and kind of regret not doing that.

But why have the rates risen? Well, there are a few hot areas, and they can be summarised as AI, analytics, mass market apps, and blockchain. I’ll discuss each briefly:

AI

This is a hot one – the idea we can replace rooms full of people doing dull and not very high value work (from the perspective of the company) such as service desks with AI bots is very attractive. It won’t work though. Most “supposedly AI” bots are just following decision trees and the only bit of AI is in parsing the meaning out of a sentence in a very tightly defined context. AI is useful today for categorisation problems – e.g. looking at a picture and deciding “this is a cat” or “this is a threatening comment”. It’s not brilliant at the job, but I like that an AI can work out which pictures are of my Mum, for example, even if it misses about a third of them… it still makes my life easier. A bit. But what an AI can’t do is right a decent blog post. Sorry, it can’t. They’re awful at it. There’s loads of AI generated content out there and it feels obviously fake. The main job of these AI generated blog posts is to trick other AIs (Google, Bing etc) into categorising a website as useful. And because AI’s make toddlers look worldly wise, they can be easily fooled… and that means you can’t trust them with anything of real importance. Like your business decisions.

But, it’s a hot keyword, and naive venture capitalists like the idea. So in comes the money.

Analytics

Tracking and stalking customers across the internet is very attractive for advertisers believing that doing so makes them seem more interesting to consumers. I’m not convinced. People often find it creepy. They feel like they’re constantly stalked. They visit the website of, say, a printer supplier and they receive ads for a month for printers… but not only for that supplier, but for other printers because the tracking provider is cheerfully using your data as a supplier against you and selling that information to your rivals! I think advertisers are starting to cotton on, but are unsure of what to do… but I know there’s a lot more direct selling of adverts between publishers and advertisers than there used to be.

But, the siren call of analytics is strong, and people love a nice chart on which to justify a decision, so the more nice charts your system can create, the more people will pay to use it and try to gain an advantage over competitors. And advertising is huge, so in pumps the money. For now.

Mass market apps

Can you build the next Facebook, Instagram, or Slack? What’s the potential for an app that lets people read books from any publisher for a fixed monthly fee? How about an app that revolutionises food delivery? Interestingly, some apps are about replacing old and inefficient intermediaries and putting new ones in place. Uber is a nice way of hiring a minicab with flexible pricing that rewards drivers for being available at the right time. They don’t disintermediate, however. The customer is both the driver and the passenger. The new intermediary takes their share.

If you can replace old intermediaries you can make a lot of money. Imagine taking 0.5% of every single financial transaction, like Visa do? That’s a lot of money. Then you have intermediaries between the card firms, providers, and networks, such as Stripe… and then there are those replacing old ones, like Wise, for money transfers across borders.

What other things can be improved? Well, literally anything.

But most attempts to build these apps and the supporting infrastructure are doomed to never turn a profit.

Blockchain

Blockchain is a really interesting concept for a public ledger, using an interesting concept called proof of work to make it hard for any one person to try to dominate the network and win the consensus mechanism on new transactions. There are theoretical ideas out there to improve on this, but at the moment they remain just that and haven’t been proven.

And it’s a scam. Pure and simple. But it’s a hot topic. Bitcoin, Ethereum, Dogecoin and many others are actively speculated upon, as well as being used for the exchange of value – often in a hope to evade regulators. It appeals to the natural rebels amongst us because it’s outside of government control… and given that governments aren’t always a force for good, I get that.

Problem is, Blockchain breaks the rules of good software development… if you look at the big O notation for software, it has to follow certain rules or it will fail at some point and need to be re-engineered. Big O matters. I don’t have academic access to papers, and the internet is full of vested interests pretending that Blockchain scales just fine. I used to see the same in WordPress land, where people said the software scaled fine… but it doesn’t. In WordPress we get scale by putting a layer between WordPress and the internet to balance things out – the work the software itself does goes up in line with the number of people talking to WordPress. We can define that as O(n) so long as you know what you’re doing – that’s OK. We can live with that. But the consensus mechanism required for multi node agreement of transactions as required to track transactions will, by its nature, follow a curve that is likely to be somewhat greater than O(n^2) (each node does O(n) work in a linear fashion but the total work done on the network as each node is added therefore grows as O(n^2) plus a bit for network latency and overheads. Yet bitcoin transaction cost isn’t following that curve in spite of huge interest because, I reckon, most Bitcoin trades aren’t real.

Yes, that’s right. And what does that mean? It’s because wideboys, crooks and the overly-optimistic are involved. Given it is, by design, a pyramid scheme, it will have to fail at some point. But people are motivated to hide that, so there are Bitcoin tracker schemes, rather like gold purchase schemes, that never hold the asset in question. They will pump and pump values as hard as you like. And as long as there are new people coming in, like our receptionists wishes to, all is good.

And there are enormous amounts of money to be made. As in a goldrush, the people making real money are the shovel makers and traders. And they need developers. So for as long as there’s money to be made, coked up wide boys will be gurning their way through stressful meetings, fidgeting and anxious to cash in before it crashes out. You can earn a lot there. For a while.

OK, so thanks for the very long essay. What does it mean then?

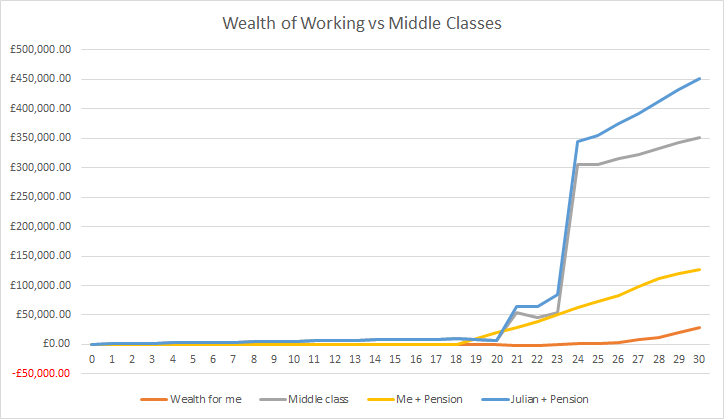

Well, it means developers are really expensive right now. Small firms that do actual useful work and aren’t highly capitalised (like mine) can’t grow because we can’t suddenly charge our customers double for the work so that we can compete against these booms. It’s as if a very rich person has moved into your town and hired all the builders possible to create a huge mansion. They even approached builders working for firms and offered them double to come build that mansion. Soon builders are all swanning around town in Teslas and feeling pleased with themselves for being so cunning as to be in the building industry.

Same in software. Locally there’s a Tesla with a crypto referencing private number plate and a young, bearded and muscular techbro driving it. Fine, I’m not going to judge. He’s happy and making good money.

But if builders are all hired by the rich, the rest of us get priced out. Same in software. Small firms are going to find they can’t afford websites unless they just use some cheap web builder platform – it’ll give a less good solution, but it’ll do the job. Ish. And the firms that can afford will do that bit better. And better. And the gap will grow.

At my firm I’ve had to raise salaries, but we still struggle to clear a profit with the raised salaries. I’m fiscally conservative, so we’ve always had decent cash reserves. This lets us ride out the storm. From 1997 to 2002 dev rates went crazy. By 2005 they were back to normal again. We as a firm can’t handle eight years of this. But it’s not quite the same as back then – you can now hire developers globally and have them work remotely, if you really wish to, which can save some money and also help those countries out with extra foreign revenue. I, however, really like quality and good communications and I find that a geographically tight team works the best. It also makes it easier to hire new people into the trade. So, for now, I’m sitting tight. I won’t seek venture capital, or borrow. And if the worst comes to the worst, we’ll add AI to something that does basic statistical analysis, and blockchain to something with two computers in the network and hope someone out there fancies throwing us some money so we join the party. In the meantime, however, there’s still a healthy living to be made as a business doing useful things and avoiding the hot trends. I never set out to be rich, merely secure – I’ll ignore the rich mansions and do my own thing, creating good code for good people.

n.b. about the above – the above isn’t a paper. It’s a set of opinions designed to inform and illuminate about what’s happened. It relies on anecdotes. Don’t take it too seriously and don’t use it as the basis for what you want to do with software and investing in software. Or crypto. Do your own thing with the information you gather from multiple sources. Also remember that a lot of people say misleading things because it’s in their interests to do so, and that you shouldn’t trust a random blog or news source on the internet. Mine included.